Romania at 99

In 2018, Romania will celebrate its centennial. Although a third of the Romanian population have no living memory of communism, the scars are ever-present. Although Romania is not considered exceptionally corrupt by world standards, it is by those of Europe. For example, according to Transparency International, Romania is the 108th most corrupt country in the world. That may not sound too atrocious, until you consider that among 30 European Union countries, Romania is considered less corrupt than only neighboring Bulgaria and Greece. When you ask a Romanian what their number one export is, they are likely to tell you “people.”

The first Romanian-born person I ever met explained it to me around the turn of the century, “Many former communist officials are still in power. They are selling off formerly state-owned assets and pocketing much of the money.” As a result, Romanians have largely forgotten Ceausescu and chosen to focus on present problems and forging an identity in the 21st Century.

Henri Coanda International Airport

Arriving at Henri Coanda International Airport was uneventful. Compared to the 47 other countries I’ve visited, passport control in OTP airport was a breeze. There was a noticeable lack of the police presence I’ve become accustomed to seeing in other European countries as well as in my own. I did not see any serious-faced military officers with machine guns, nor was I hassled during passport control. Another thing that was lacking was smiles on the faces of those coming and going as well as the people working at the airport.

Since I was in Bucharest on a press trip, I was greeted at the airport by a driver. There was very little conversation during the ride into the city. The ride itself was much smoother than the chiropractor visit inducing rides I’m used to when going to JFK and Newark International airports in the greater New York City Area. My other observation from the 20-minute ride was that very few square feet within 10 feet of the ground were untainted by graffiti. Although I love street art, most of what I saw appeared to be vandalism rather than art.

Vlad Dracula vs. Nikolai Ceausescu

Late in the afternoon during my first full day in Bucharest, my group was taken on a free tour of the old city. Historically speaking, the tour went back as far as the times of Vlad Dracula up to the present. Carmen, our tour guide, was an enthusiastic Brasov-native with a passion for all things Romania; good, bad and gruesome.

One of our stops was the ruins of Vlad Dracula’s citadel. Carmen pointed out how Vlad “The Impaler” ordered the impaling for more than 20,000 Ottomans. According to her, “Dracula was a bad guy, but he was our bad guy. He only impaled bad people. For example, the Ottoman Empire had been the historical enemy of Romania dating back more than 500 years. Few were willing to shed tears for the Ottoman invaders.”

Like Dracula, Nikolai Ceausescu was a strong, cult of personality leader with autocratic tendencies. Although their reigns were 500 years apart, the two are perhaps the most well-known Romanians to the outside world. While Dracula died fighting for his people, Ceausescu was executed by his subordinates along with his even less-popular wife.

Street Art in Bucharest

Since the fall of communism, a street art scene has emerged in Bucharest, spearheaded by artists like the Sweet Damage Crew. During my second full day, I explored the street art in the city. My guide was Elena, who is an enthusiastic mother of two who considers her tour guiding time to be her “holiday.”

At the beginning of the tour, Elena pointed out that, “Like most capital cities, Bucharest is a collection of neighborhoods known as mahallas.” When I asked her when street art became prevalent in Bucharest, she mentioned that “During communist times, there were no people begging in the streets, nor were there people spray-painting buildings. People were not allowed to express themselves in that way.”

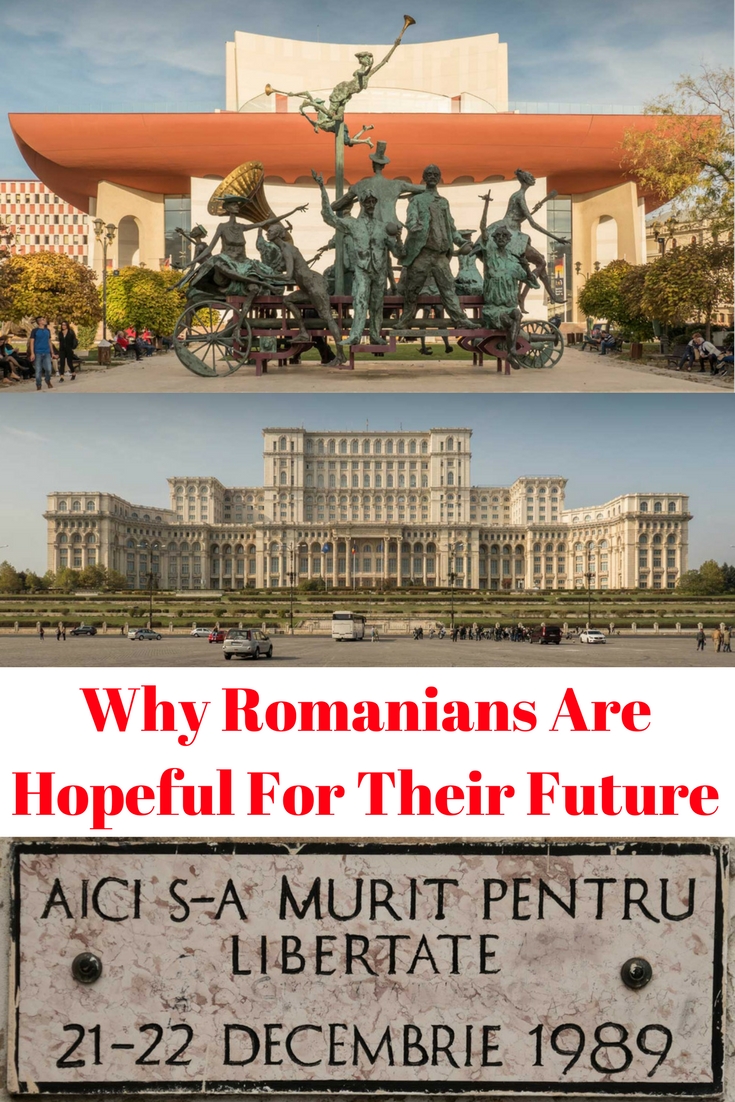

Revolution Square in Bucharest

After winding through different mahallas, we ended our tour at Revolution Square in the city center. That was when the conversation got really interesting. Elena pointed out that we were standing near the spot where Romanian dictator (or President, or General Secretary of the Communist Party), Nikolai Ceausescu had been bragging to the people how he paid off the national debt and that Romania was truly independent. “By 1989, people were more interested in fuel to heat their homes and food to eat than the national debt. For the first time, someone started shouting at this all-powerful dictator,” she said.

Romanians in Pennsylvania

I was in my late teen years when I met my first Romanian. Eastern Pennsylvania, where I grew up, has a large population of Romanians who fled both communism as well as the chaotic aftermath. Her name was Marta, and I remember her telling me stories about her being forced to do patriotic chants in the classroom. “If you didn’t join in, you were ridiculed. My family left for religious freedom. I believed that one in every ten people was a spy. The revolution started in my hometown of Timisoara. Only a couple years after my entire family was safely in the United States. I remember my family being shocked when the Ceausescus were executed. They were in power for a quarter-century.”

My neighbors since 2014 are also from Romania. When I told them I was visiting, one of them responded, “Years ago, everyone had a job. Nobody was begging in the street. Now the country is very corrupt. You have to watch your pockets. If people think you have money, they may try to take advantage of you.”

Before leaving for Bucharest, I recalled that conversation to Marta. She didn’t deny any of it. She elaborated, “There was a respect for authority figures. You respected your teacher. The only people in the street were drunks, who were eventually taken home by the police.”

To me, this brought up a universal theme of how much freedom are people willing to exchange for order and security. My refrigerator is covered with magnets from my travels over the past 17 years. One of my favorite magnets has nothing to do with travel. It’s a quote from Benjamin Franklin: “Anyone who will give up freedom for security deserves neither.” The wounds of the communist era seem fresh enough that Romanians are not willing to give up their relatively newly won freedom for order under authoritarian rule.

The Romanian Middle-Class

My second tour of the day was provided by Ioan, at twenty-something local guide who grew up in the post-revolution chaos, and his partner, Andrea. Ioan grew up in an upper-middle-class family and had what he described as a happy childhood. “I was born and raised on 13th September Street in the last big neighborhood built by the communist regime. In many ways, the cost of building this expensive area combined with the national debt led to Ceausescu’s downfall. The 1980s were a very tough time for the average folk with the shortages of food, heat, and electricity.”

After a leisurely stroll through Carol Park, we made it Ioan’s old neighborhood. Referring to his childhood, he explained, “Most of us were upper-middle-class. We had a lot of privileges. Most of the people that lived here when I was a kid were footballers, secret service agents, pop stars, or middle management from the state-owned companies. My father worked for the state-owned tourism company and eventually became president.” The only bad memory Ioan mentioned was when his father was fighting against privatization of the state-owned tourism company, and someone tried to torch their home.

He also recalled being segregated from the Roma population. In his own words, “We didn’t go where they lived, and they didn’t come where we lived. I can’t remember if we rejected them, or if it was just some unwritten rule. Either way, there was almost no interaction.” Ioan’s other memories from childhood included playing games like hide-and-seek, ducks and hunters (similar to dodgeball), and games I’d never heard of like thick milk and elastico.

Palace of the Parliament

Eventually, we made our way to the infamous Palace of the Parliament. As Ioan put it, “To Romanians, this was the ultimate showcase for Ceausescu’s megalomania.” When I grinned, he looked in my direction and said, “Only your Pentagon in Washington, D.C. is bigger.”

Perhaps the true tragedy is what the building still costs the Romanian taxpayers. As Ioan rattled off the staggering figures, I asked if part of it would be better put to use as a hotel. For three nights of the trip, I stayed right across the street and had to walk past the building on the way to the nearest metro stop. I can imagine tourists bragging that they slept in the House of Parliament building. However, Ioan insured me that it will probably not be converted into a hotel anytime soon.

Ceausescu’s Fateful Visit to North Korea

Ioan continued, “After Ceausescu visited North Korea, the cult of personality really took effect. Romania had to have big monuments like Pyongyang does. When I got back to my room later that night, I watched a YouTube video of Ceausescu’s 1971 visit to Pyongyang. Like Ioan mentioned, the Koreans memorized the Romanian national anthem. What looked like football stadiums full of people watched his motorcade. Perhaps, Ceausescu needed some of that same affection when he returned to Romania. He needed to be worshipped at home, like Kim Il Sung and later, his son were in North Korea. After watching the video, I could hear Marta’s husbands words ringing in my ears, “the 1980s were the worst decade for Romanians.”

The Dark Side of Bucharest

The two most famous Romanians were a man nicknamed “The Impaler” and a communist dictator, both of whom died violently. While Romania is not all death and torture, my final tour faced those issues head-on in ways that would not have been possible just 30 years ago.

Our group’s guide was Emma, an energetic twenty-something with a passion for history. Although she was born two months before the end of Ceausescu’s quarter-century reign, through her parents, she’s able to speak about communist times with the zeal of someone with curiosity, yet without the negative emotional baggage of someone who lived through it. In her own words, “Communism left deep scars on the locals. It’s unbelievable how different my country is today, compared to when my parents were my age.”

At the end of that tour, Emma asked if there were any more questions. When nobody raised their hand(s), she thanked everyone for coming. I stayed behind and asked the question, “Where did people get their clothes?” This innocent question led to fairly long and interesting conversation. “My Mom and Dad each had one pair of jeans. They were an exotic item,” Emma told me matter-of-factly. “What if they ripped?”, I asked. Knowing where I was taking the conversation, she replied, “In those days people knew how to fix things. You didn’t just throw things away. For example, my mother knew how to sew. If a button popped off, you sewed it back on.”

Before we parted ways, I had one final question for her: “why do you choose to stay in Romania?” I asked this question because she has degrees from two different public universities and has other options. She responded: “I like my country and the people here. I hope things will change for the better. I see big potential in Romania, and the recent economic growth confirms that. Life in Bucharest is very exciting for me, and I love what I do.”

Tourism and the Future of Romania

During my week in Bucharest, I met dozens of Romanians. A few of which I had detailed conversations with. Andrea, Carmen, Elena, Emma, and Ioan all have a handful things in common: no living memory of communism, dedication to educating people about the good, the bad, and the system that dominated life in Romania for more than 40 years, an uncertainty of what Romania’s future will be, frustration about the status quo, and most importantly, hope for the future.

People like Marta and her husband, as well as my neighbors, seem perfectly content in the United States. Although the years of dictatorship are older than a third of the people living in Romania, none of the people that left in my lifetime seem eager to go back for more than a visit. However, I met many people younger than me who were full of hope and eager to shape the future.

Tourism is a growing part of the Romanian economy. Andrea, Carmen, Elena, Emma, and Ioan all make their livings from tourism. Years before I visited Romania, I had asked Marta whether or not she suggested visiting. Her answer was an adamant yes: “It’s a beautiful country with a lot of history and breathtaking landscapes.” However, Romania needs to become more than, “It’s a nice place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to live there.” Tourism can only take a country so far; especially a country as large as Romania. The former communist officials, who are still in power are getting older and won’t be around much longer.

This post was sponsored by Experience Bucharest and Urban Adventures. For tours similar to those described in this post, check out Bucharest Urban Adventures.

As if the USA has freedom, bullshit. Hold a sign up that actually challenges the government in a city park no less or try to buy or sell recreational drugs other alcohol, tobacco, sugar and cow milk. The USA is a plutocracy and dictatorship managed by Republicans and Democrats. Meat is murder, you call the 9.5 billion animals murdered and tortured in the USA every year proof of freedom?