The Soviet Union in the 1980s

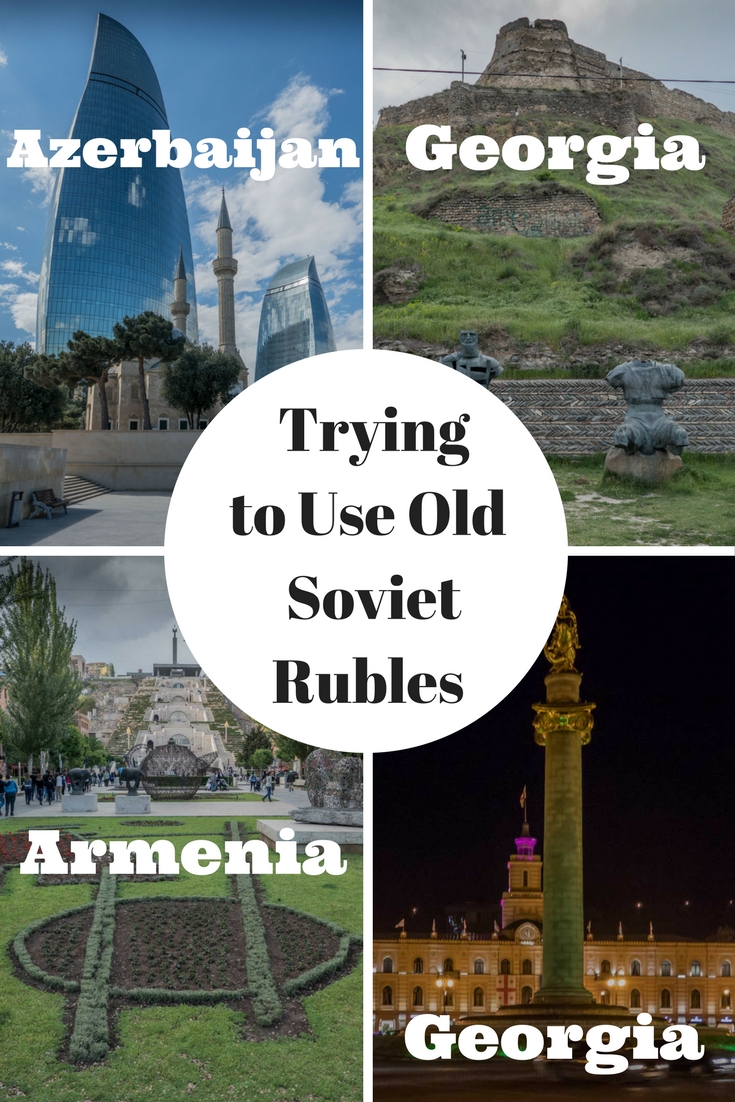

My six years of elementary school were also the final six years of the Soviet Union. Every day, my classmates and I were drilled with the idea that we are free and the rest of the world is not. Twenty-six years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, I had the chance to visit three former Soviet Republics: Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. Although I was excited to see the capital cities and ride the rails, I was most interested in seeing how the people I met felt about their time as part of the USSR.

Tbilisi, Georgia

Yerevan, Armenia

Baku, Azerbaijan

Yerevan Vernissage

My way of experiencing a city is to head first to a local market, preferably via public transit. It was a sunny Saturday afternoon in Yerevan, Armenian’s capital. After the short walk from Republic Square, I arrived at Yerevan Vernissage, a famous weekend market. The dozens of vendors sell cheap souvenirs like magnets and teacups as well as paintings, pottery, and rugs. After buying a half-dozen magnets for friends and family back in the states, I came across a graying elder gentleman who sold old coins and paper bank notes. As an avid currency collector, this was my spot. There was no shade, but I didn’t mind the afternoon sun beating down on my balding, unprotected head. As I made eye contact with the gray-haired man who looked older than many pensioners, my smile must have been apparent. He had rubles from the old Soviet Union bearing the face of Vladimir Lenin.

Soviet Rubles For Sale

Back in elementary school, I’d been taught what an evil man this Lenin was. Just like when I saw the Yasser Arafat museum in Ramallah two months prior, I knew that one person’s villain is another’s hero. However, I sensed that this man was not selling old Soviet money for ideological reasons any more than vendors in Jerusalem’s Arab Quarter sold pictures of Yasser Arafat. I asked him the price with an eager smile on my face. When he responded with a hand gesture indicating five notes for 1,000 Armenian dram, I was not in the mood to bargain. We had a deal.

The Armenian Genocide Museum

My next destination was the Armenian Genocide Museum, which is not easily accessible by public transit. A taxi was the best option, so I walked back to Republic Square and quickly found a taxi with a gray-haired man behind the wheel and an American flag air freshener hanging from the rearview mirror. The driver spoke little English, but that didn’t stop him from trying to carry on a conversation with me in his native tongue during most of the five-minute cab ride. We rode uphill, and I was more focused on the breathtaking view of the city than whatever he was trying to tell me.

Taxicab Drivers in Yerevan Prefer Armenian Dram

When we arrived, instead of paying the cab driver the 700 dram he asked for, I whipped out ten old Soviet rubles and handed the bill to him. At first, he seemed to think I was serious. Through the window, I saw two police officers standing in front of a tour bus as he said “no good” and looked back at me and then handed me the bill. I acted puzzled before giving him 1,000 dram. Once he knew he was going to get paid, he started laughing and then waived the police over. Although an interaction with police in a foreign country may be scary to many, the mood was way too lighthearted to incite fear. Although the dialogue between the officers and the cab driver was indecipherable, one of the policemen who looked as if he hadn’t missed too many days at the gym waived for me to show him something. Assuming he wasn’t asking for my passport, I showed him the ten rubles. Both officers had a 30-second laugh before handing back the money. I remember wishing that I could speak to them, but Yerevan is not used to getting many tourists. In fact, Yerevan is within a day’s drive from both Turkey and Azerbaijan, but neither border is open.

Armenia in the Soviet Union

After touring the somber genocide museum, I needed a ride back down into the city. I couldn’t resist trying my luck again. My next cab driver had a similar appearance to the last, but this time, there was a Brazilian soccer air freshener hanging from the rearview mirror. This driver had a similar build, with salt and pepper hair and was also trying to converse during the whole trip. When I tried to pay him with the old rubles at the end of the ride, he burst into laughter behind his dark shades. Later on that evening, I took a walking tour of the city. My guide explained that Armenia was eager to join the Soviet Union in exchange for protection against Turkey. Like the two cab drivers, my guide was lighthearted and had an obvious sense of humor, never taking himself too seriously.

Tbilisi, Georgia

Another sunny day in another sunny Caucasian capital. Georgia gave the world Joseph Stalin as well as wine; depending on who you ask. After visiting the Museum of Soviet Occupation in Tbilisi, I took a leisurely stroll through the old city. I had been disappointed with the lack of fresh-squeezed juices available when I came across a middle-aged, gray-haired woman, selling fresh squeezed orange juice. The price was ten lari. In the 60 or so seconds since I placed my order and watched her squeeze the orange juice into a paper cup, she did not crack a smile. But after a visit to Yerevan, even my fellow North Americans may seem unfriendly. When she opened her withered hands to show me all ten of her fingers, I handed her ten old Soviet rubles. She stared at the note like I had just handed her a piece of trash that I was too lazy to dispose of myself. After a brief examination, she handed it back, pulled 10 lari out of her purse to show me what she wanted. After I obliged, she broke into a slight grin and shook her head.

Georgia as a Soviet Republic

Before departing for Baku, I took a free city tour of Tbilisi. The young, bearded, hippy-looking guide was too young to recall Soviet times, but interestingly enough, did mention that Stalin was not considered a hero outside of his hometown of Gori. For three hours, he showed us his city and focused mostly on history before and after Georgia’s years as a Soviet Republic. The message seemed clear: the Soviet occupation was a dark period in Georgian history.

Baku, Azerbaijan

My tour of the Caucuses ended in Baku. Visiting the Azerbaijani capital was the most complicated part of the trip. I had to get a visa and could not enter through Armenia since the border has been closed since 1988. In fact, the two countries are still technically at war.

Pranksters Aren’t Welcome in Baku

Upon arrival in Baku, the results of the recent oil boom were apparent. It seemed to be a city with something to prove to the world. With the somewhat artificial-feeling waterfront along the Caspian Sea and more skyscrapers than I saw in the previous week I spent in Armenia and Georgia, Baku seemed eager to leave its Soviet past behind. Besides a construction boom, two things stood out: the lack of smiles and an intense police presence. The few Americans I met who visited Russia during Soviet times all had one common observation: nobody smiles. One can even observe that by spending an afternoon in Brooklyn‘s Brighton Beach. Baku felt like the kind of place where pranksters aren’t welcome. In fact, the day I arrived, I took a short video of a metro train arriving and three police officers quickly approached me and made me remove the photo.

The Flame Towers in Baku

The tourist in me had to ride the funicular up to the Flame Towers before I did anything else. When I stood in line to board the funicular, it seemed like the first time tourists may have outnumbered locals in Baku. As I approached the balding, middle-aged attendant in his black pants and light blue button down, uniform shirt, I noticed that his lips remained sealed like The Go-Gos. I handed him the ten old Soviet rubles and his lips remained sealed while he motioned “no†with his index finger. Another guy not in the mood for jokes. I tried my luck one more time when I had to take a taxi back down to the city center. Again, no laughs, just a driver who wanted to get paid and get on with it.

Azerbaijan as a Soviet Republic

The next day, I took a free walking tour and was informed of the Soviet invasion on April 28, 1920, as well as the massacre by Soviet troops in January 1990.

I Took My Soviet Rubles Back to America

In summary, there were two extreme reactions to my attempting to pay for goods and services with old Soviet rubles. The Armenians reacted with lightheartedness and a sense of laughing with me rather than at me. Conversely, the Azerbaijan’s found no humor in my attempt to gauge their feelings about their Soviet past. The Georgians relationship with their old Soviet overlords was much more complex, given that Stalin came from Gori and one of the main roads there bears his name. However, outside of Gori, Georgians saw no need to glorify their years as a Soviet Republic. Between Georgia’s attempts to join the European Union, the cheerful optimism of the Armenians and Baku being touted as the next Dubai, the three former Soviet Republics known as the caucuses are looking forward rather than to the past.

This was a super interesting little experiment! I know Armenia well, like the other republics they are not exactly known for smiling, so cool that you had a different impression. I will say that most Armenians have a good sense of humor so while they might not smile just walking around on the street they know how to take a joke! I’ve been to the Stalin Museum in Gori, and while the English language guide was clear to talk about the horrors of Stalin’s rule (after the museum received criticism for what was seen as an overly pro-Stalin spin), I am told the Russian tour is still quite pro-Stalin. I wonder if the same effect was on display with your tour. While the young hipster probably has no ties or reason to glorify Stalin, I wonder how Russian language tours would have gone. I don’t think Stalin is only a hero in his hometown in Georgia, maybe not everyone but certainly some outside Gori. Not surprised about the reaction you had in Azerbaijan at all. The nation has a somewhat insecurity problem and so that probably translates to an over-sensitivity or lack of humor about things. The fact it is a dictatorship led by a cult of personality probably doesn’t help much either with the humor thing. I know I’m generalizing here, and maybe you would have found some Azerbaijanis who would have laughed over it, but I’m not surprised you didn’t.

BTW I’m from outside Philadelphia too! I found this blog from Twitter after looking up Armenia.

Glad you found it via Twitter. I still try to visit Philly a few times every year.

hahhaa! Nice experiment you had here. It was an interesting read. Better luck next time mate! I absolutely enjoyed reading your experience.

Hi Jeenu. Not sure about Armenia and Azerbaijan, but I will go back to Georgia.

To be honest, i was unaware of history and facts that you mentioned about Soviet Union in late 1980’s, thanks for sharing your experience with us 🙂

Hi Kailash. You are welcome.

Interesting experiment, I bet both countries were pretty confused when you tried paying for them. They’re a great part of history to keep though x

Thanks Rhian. I try to take at least one of the smallest paper note from wherever I travel. I have some that are no longer in use. Like the old rubles.

Wow…it is such an awesome post to read. I am planning to visit Georgia in September first week and I am sure I am going to remember your experience there. Love the experiments!

Of the three countries, Georgia had the best food. I eat it often in New York to this day!

Oh that’s an interesting experiment you had there. It must have been so interesting to see their reactions when you tried to pay by old currency. Thanks for this wonderful read. 🙂

Hi Aditi. Glad you enjoyed this story.

Thanks for sharing your experience. I live in Poland and I have an impression that Armenia and Azerbaijan are not very famous and not a lot of people travel there. For sure Georgia is pretty interesting destination for a lot of people. I would love to visit these countries one day to expand my knowledge and learn something new.

Best,

Kasia

Hi Kaisa. I recommend starting in Georgia or Armenia. Leaning towards Georgia.

It was the amazing experiment I believe. The one you try with driver When you stood in line to board the funicular, is one liked the most.

The funicular ride was fun. They have a nice metro in Baku as well.

Thank you for sharing. You seem like you have an interesting experiment there. It was a very detailed post and I enjoyed reading it!

Thanks Wynne. Glad you enjoyed reading this piece.

An interesting read it was, It seem like you have an interesting experiment there, It must have been really interesting to see their reactions 🙂 Thanks for sharing.

Hi SJ. It seemed like harmless fun.

This is an interesting read for sure… I am wondering why you referred to them all as caucasian places though rather than just mentioning their history.

They are between the Black and Caspian seas.

Haha what an interesting post and lovely little experiment. I like your writing too, it was such a light read, made me smile. Good post!

Glad you appreciate it! Have you been to those countries?

This is such an interesting read! I smiled at the part where you tried to pay the taxi driver with Soviet Rubles. I am definitely super interested in visiting these places and learning about the rich history!

Yes, and all three are relatively affordable.

Captivating read and I’m sure you had a blast of experience! I’d love to visit the country someday because of the history she holds!

I recommend doing Georgia first. I only saw 3 cities and the trip was rushed.

This was a super interesting and informative read! There is so much history to learn. Great photos and videos too, thanks for sharing 🙂

Glad you like the photos. I shoot raw with a Panasonic Lumix.

Interesting read, Brian. I learnt some stuff and you made me laugh. I remember when you first saw these videos . So funny! I’m glad you made it out alive to write about your experiences 😀

Thanks Cristal. I never felt threatened. Just be careful with the Armenia/Azerbaijan situation and you’ll be fine.

This was funny in a way. I would like to visit these places one day and learn about their rich culture.

Hi Elena. Minus the border situation between Armenia and Azerbaijan, they are easy to combine into one trip.

Super interesting to read this! Interesting observations and funny trying to pay in the old currency! Really interesting post!

Thanks Juliette!

This is so informative. I didn’t know much about history of these places and yeah i realize that they really have a rich culture.

Thanks Alice. Hope you get to visit as well.

Wow…pretty brave with your tests. Not sure I have the same gumption given the history many have in those parts with the Soviet union.

I always ended up paying the correct currency in the end.

Wwow amazing experience you had. Has been a good reading

Thank you!

In the former Soviet republics, money has changed so many times. Old money is only interested in collectors, and ordinary residents need real money for life 🙂

Now in Russia, residents do not believe even banknotes in 2000 and 200 rubles, which were issued only recently. Because they saw these banknotes only in pictures.

Hi George. Thanks for commenting. How is the cruise business?